Forensic investigations can leverage DNA-based kinship methods to develop investigative leads when direct identification from a crime scene sample is not possible. Familial searching (FS) and forensic genetic genealogy (FGG) both use kinship relationships to generate leads but differ significantly in scope and application. FS focuses on identifying close, first-degree relatives using government databases, while FGG extends search to distant relatives via privately maintained databases of dense single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profiles.

Despite their fundamental differences, FS and FGG are sometimes mentioned interchangeably in media and general discussions, which can lead to misunderstandings. Because these methods operate so differently and are suited to distinct investigative needs, it is essential to differentiate them clearly. This post clarifies how these methods work, highlights their differences, and explores when each is best suited to forensic investigations.

Direct DNA Comparisons in Forensics

The foundation of forensic DNA analysis involves directly comparing a DNA profile from a crime scene sample to a reference profile from a known individual. This one-to-one comparison relies on having DNA from a specific person and is widely used in forensic casework. Another common comparison, a one-to-many search, is used in national databases like the National DNA Index System (NDIS) within CODIS (Combined DNA Index System). CODIS stores DNA profiles from convicted offenders, arrestees, and forensic evidence and enables cross-referencing at local, state, and national levels.

CODIS profiles are built using STRs (short tandem repeats), which are repeating DNA sequences highly variable between individuals. STR profiling effectively differentiates individuals and close relatives; however, if the crime scene DNA has no match in CODIS, the investigation may not gain any leads from this approach.

Familial Searching: Limited Scope for First-Degree Relatives

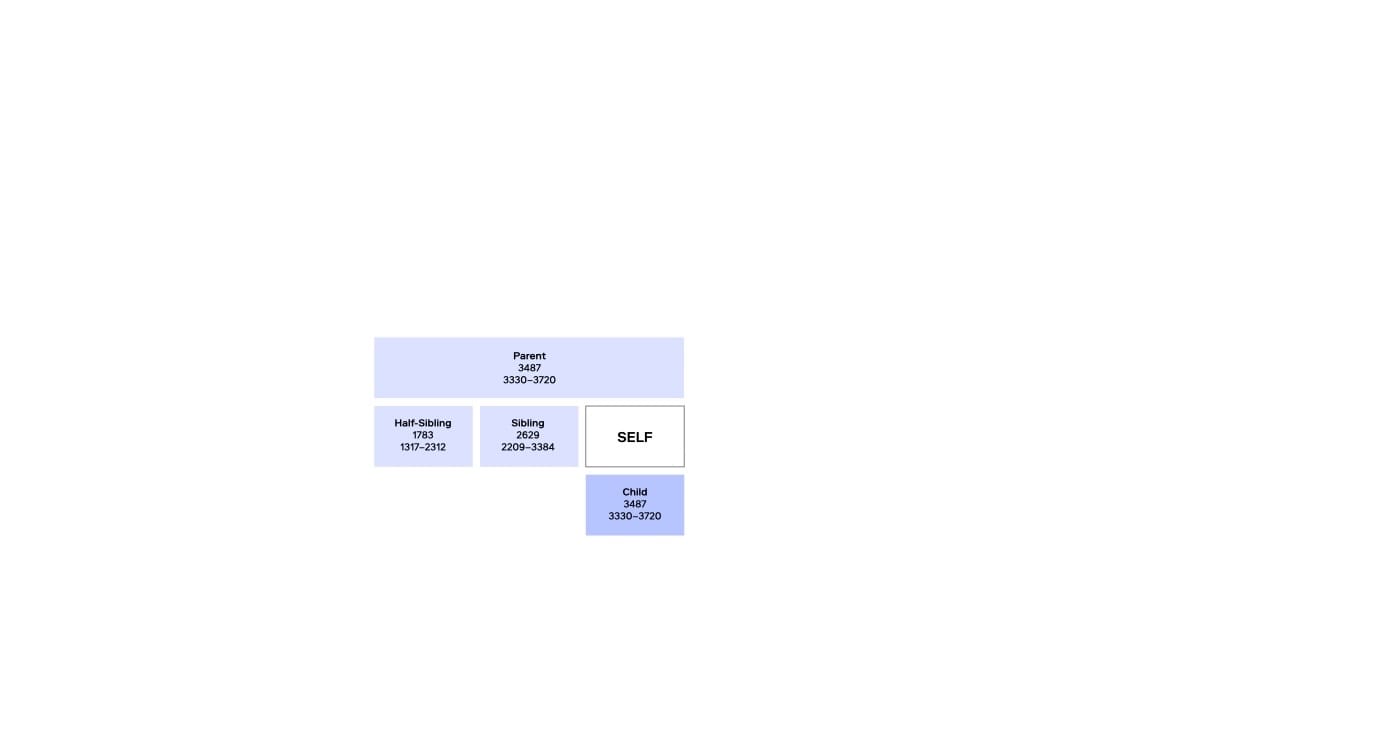

Since the early 2000s, familial searching has been used to broaden the scope of CODIS searches when no direct match is found. FS is a kinship-based approach that examines genetic similarities in STR profiles to identify potential close relatives of a forensic DNA profile. By comparing a forensic profile against CODIS, FS can detect first-degree relationships, such as a parent, child, or sibling.

FS has led to notable case breakthroughs, like the Grim Sleeper case in California, but its effectiveness is limited to identifying very close family members. FS typically requires follow-up Y-chromosome STR testing to confirm relationships and reduce adventitious hits—instances where unrelated individuals have similar STR profiles. Additionally, FS is permitted in only a dozen or so U.S. states and is therefore not widely available.

This was a problem, for example, in New York. In April 1981, the remains of an unidentified man were discovered near Vadney Farm in Delmar, NY, leading to an investigation by the Bethlehem Police Department that spanned decades. Initial efforts to identify him were unsuccessful, and the case went cold. In 2013, the investigation was re-opened, and an STR profile was developed and submitted to both State and National databases to generate leads. However, a request to compare the DNA with any potential familial DNA on file was denied due to New York State policy, which at the time did not allow for FS. Bethlehem Police later partnered with the FBI and Othram to use FGG, ultimately identifying the man as 41-year-old Franklin D. Feldman. This case helped change policy in New York and familial search has since been permitted in the state.

Forensic Genetic Genealogy: A Force-Multiplier for Forensic DNA Investigations

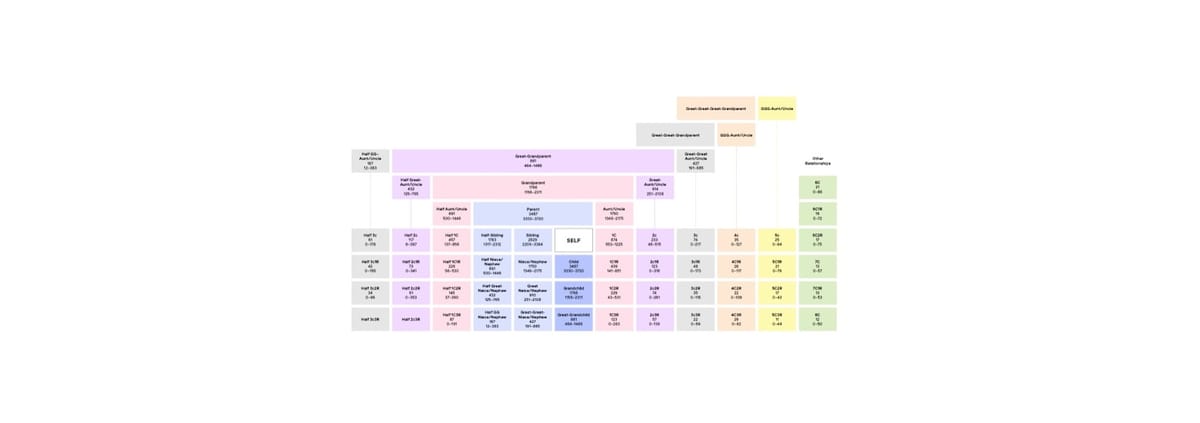

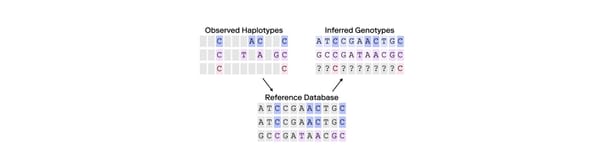

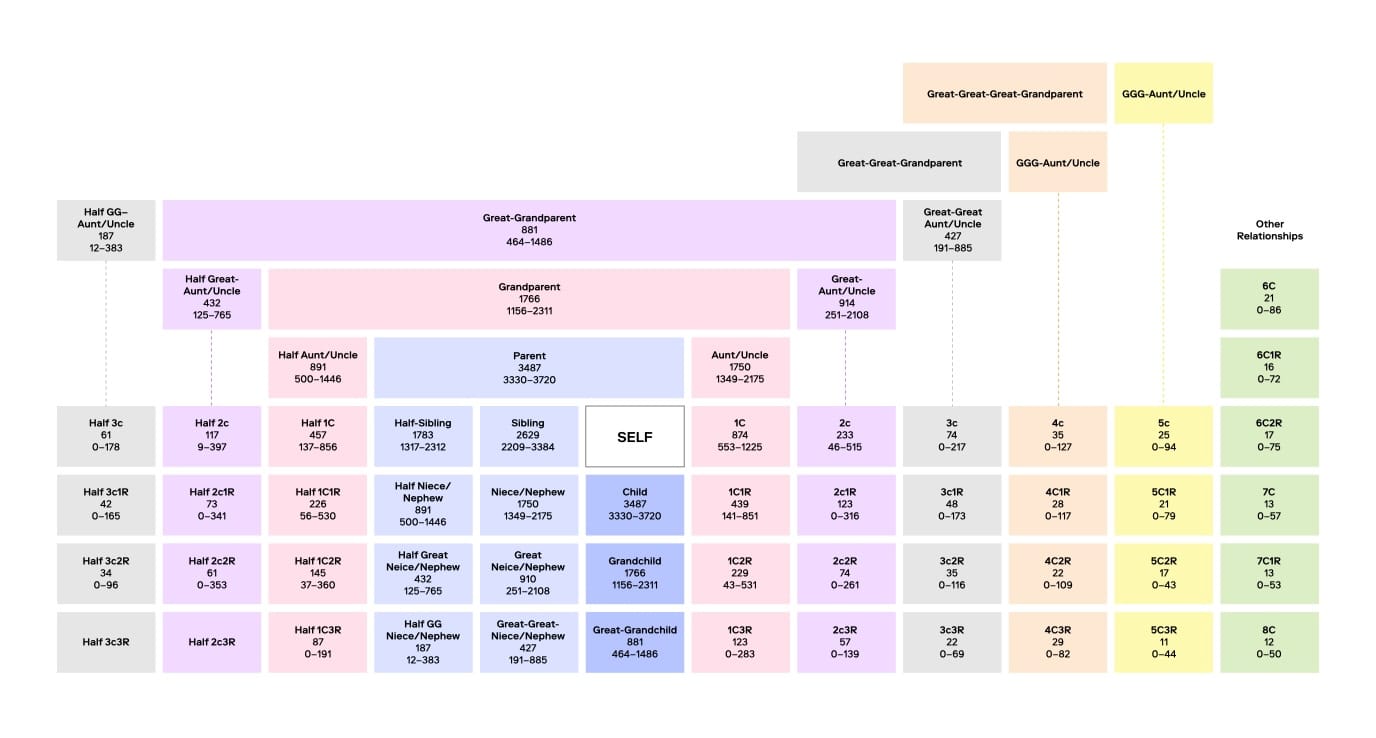

FGG extends kinship searches beyond close relatives by analyzing SNPs rather than STRs. SNPs are single nucleotide variations across the genome that offer a more comprehensive view of genetic relationships. Unlike STR profiles, which contain around 20-30 markers, FGG can analyze hundreds of thousands of SNPs, allowing forensic experts to identify relationships as distant as sixth cousins. This approach vastly increases the pool of potential leads.

A key distinction in FGG is the use of privately managed databases comprising profiles of individuals who have consented to law enforcement access for unsolved investigations. Additionally, forensic samples are often incomplete or degraded, and FGG can be applied in conjunction with specialized search algorithms, such as those in Othram’s Multi-Dimensional Forensic Intelligence (MDFI) platform, to enable searches that would otherwise not be possible with traditional forensic DNA testing methods.

Choosing the Right Tool: Considering Sample Quality and Population Representation

While FS and FGG each have strengths, they differ in scope and limitations, making them suitable for different scenarios:

- Population Representation: FS relies on CODIS, which includes a broad population range but is limited to identifying close relatives. In contrast, FGG databases predominantly contain profiles of European ancestry, which can make FGG more challenging for underrepresented populations.

- Sample Quality and DNA Type: FS requires STR profiles, which need higher-quality, larger DNA fragments for accurate analysis. FGG, by analyzing SNPs and working with shorter, more degraded DNA, is better suited for aged or compromised samples often found in cold cases.

- Degree of Relationship: FS identifies only first-degree relatives, whereas FGG can establish connections to more distant relatives, broadening the search when immediate family members aren’t available or no longer living. Additionally, CODIS is unlikely to hold the identities of human remains, as these profiles are typically those of victims rather than suspects.

Two distinct paths to kinship testing in forensics

FS and FGG, while distinct in application, serve as complementary approaches in forensic investigations. FS provides a structured, STR-based search within CODIS, making it ideal in situations where minimal or no DNA evidence remains or where investigators aim to maximize the use of existing CODIS-compatible profiles. Because FS uses the same STR profiles as traditional CODIS one-to-one searches, it can proceed without needing additional DNA material.

On the other hand, FGG expands the reach of investigations by leveraging SNP data and identifying more distant relatives, making it suitable for cases where DNA quality and quantity are limiting. When a crime scene sample is too degraded for STR analysis, or when no close relatives are available, FGG provides an alternative that can yield extensive family connections, even up to distant relatives.

The choice between FS and FGG depends on factors like DNA quality, population representation, and relationship scope. Together, these kinship approaches offer flexibility to adapt investigative strategies to the circumstances of each case, broadening the potential to identify leads and bring resolution to unsolved cases.

If you are looking to explore FGG for your case, come to Othram. Our team operates the world's first purpose-built forensic laboratory for forensic genetic genealogy. We developed Forensic-Grade Genome Sequencing® or FGGS® to enable ultra-sensitive detection of distant relationships. It's part of our Multi Dimensional Forensic Intelligence (MDFI) platform.

More forensic genetic genealogy cases have been solved with Othram FGGS® than any other method. Let’s work together to unlock answers and bring justice to those who need it most. Get started here.