Forensic genetic genealogy (FGG) is a force-multiplier for law enforcement investigations, offering powerful new tools to identify unknown individuals, deliver justice, and bring closure to families. The recent introduction of the bipartisan Carla Walker Act in both the House and Senate marks a significant step forward in supporting this transformative technology. This legislation not only honors the legacy of Carla Walker—a victim whose cold case was solved through FGG—but also aims to ensure that this cutting-edge approach is more accessible, effective, and widespread in law enforcement investigations.

Carla Walker's Murder: A Pivotal Case in FGG

Carla Walker’s case serves as a major milestone in forensic genetic genealogy, not only for its resolution but also for its broader implications for the field. Carla was abducted and murdered in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1974, and for decades her case remained unsolved. Initial attempts to generate a DNA profile from evidence collected at the crime scene were unsuccessful, underscoring the challenges of working with degraded forensic samples. These early failures highlighted a critical gap in the forensics community: the lack of standardized data collection and reporting on methods that succeed and fail when analyzing challenging samples.

The Carla Walker Act addresses this gap by requiring transparency and accountability in forensic investigations. By mandating the reporting of successful and unsuccessful attempts at DNA analysis, the legislation aims to create a robust knowledge base that can guide future cases, improve methodologies, and ensure that resources are directed toward techniques that work.

In 2020, after initial failure, Othram’s forensic DNA testing technology enabled investigators to develop an ultra-sensitive DNA profile from the evidence using FGG. This breakthrough led to the identification of Glen McCurley Jr. as Carla’s killer. McCurley confessed to the murder in 2021 and was convicted, bringing long-overdue answers and justice to Carla and her family.

The Carla Walker case was significant not just for its outcome but for its legal implications. It was one of the first cases where FGG was presented in a courtroom setting. The use of FGG underwent a Daubert hearing—a legal process in the United States that determines the admissibility of scientific evidence in court. During this hearing, the judge acts as a gatekeeper, evaluating whether the methodology meets several criteria to ensure it is sound and reliable. After being admitted by the judge, FGG evidence was presented during the jury trial, where scientific experts explained the methodology and were subjected to cross-examination.

McCurley’s conviction was later appealed, and an appellate court upheld the verdict, reinforcing the legal robustness of FGG. The successful use of FGG in the Carla Walker case set a precedent, showcasing its potential as a powerful tool for solving cold cases and securing convictions in the courtroom. This case not only demonstrated the technology’s investigative value but also paved the way for its acceptance in the legal system, ensuring that FGG can continue to deliver justice in cases where traditional methods fall short.

How Forensic Genetic Genealogy Works

FGG identifies unknown individuals by analyzing shared blocks of DNA, called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), to trace familial relationships. Unlike CODIS, which relies on short tandem repeat (STR) markers to find direct matches to known offenders, FGG leverages the power of SNP analysis to connect distant relatives through genealogical databases. You can learn more about the differences between STRs and SNPs here.

This approach has already solved numerous cold cases, but scaling FGG requires substantial investment and federal leadership. CODIS, now a gold standard in forensics, was made possible through hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funding that supported infrastructure, public laboratory capacity, and nationwide implementation. Similarly, FGG needs coordinated federal support to build the infrastructure, establish best practices, and ensure equitable access to this life-saving technology.

The Carla Walker Act seeks to provide this leadership by funding pilot programs that support forensic genome sequencing for samples that failed traditional testing, making FGG accessible for more cases. For a deeper dive into the role of federal leadership in advancing forensics, read our post: Why Federal Support is Critical for the Future of SNP Testing in Forensics.

The Carla Walker Act: A Framework for Federal Leadership in FGG

Introduced with bipartisan support in both the House and Senate, the Carla Walker Act establishes two yearly $5 million pilot programs aimed at funding forensic genome sequencing and forensic genetic genealogy (FGG) for unsolved cases. These programs are designed to empower law enforcement by providing access to cutting-edge technology, including state-of-the-art laboratory services, modern sequencing equipment, and advanced methodologies for solving challenging cases that traditional forensic methods cannot address.

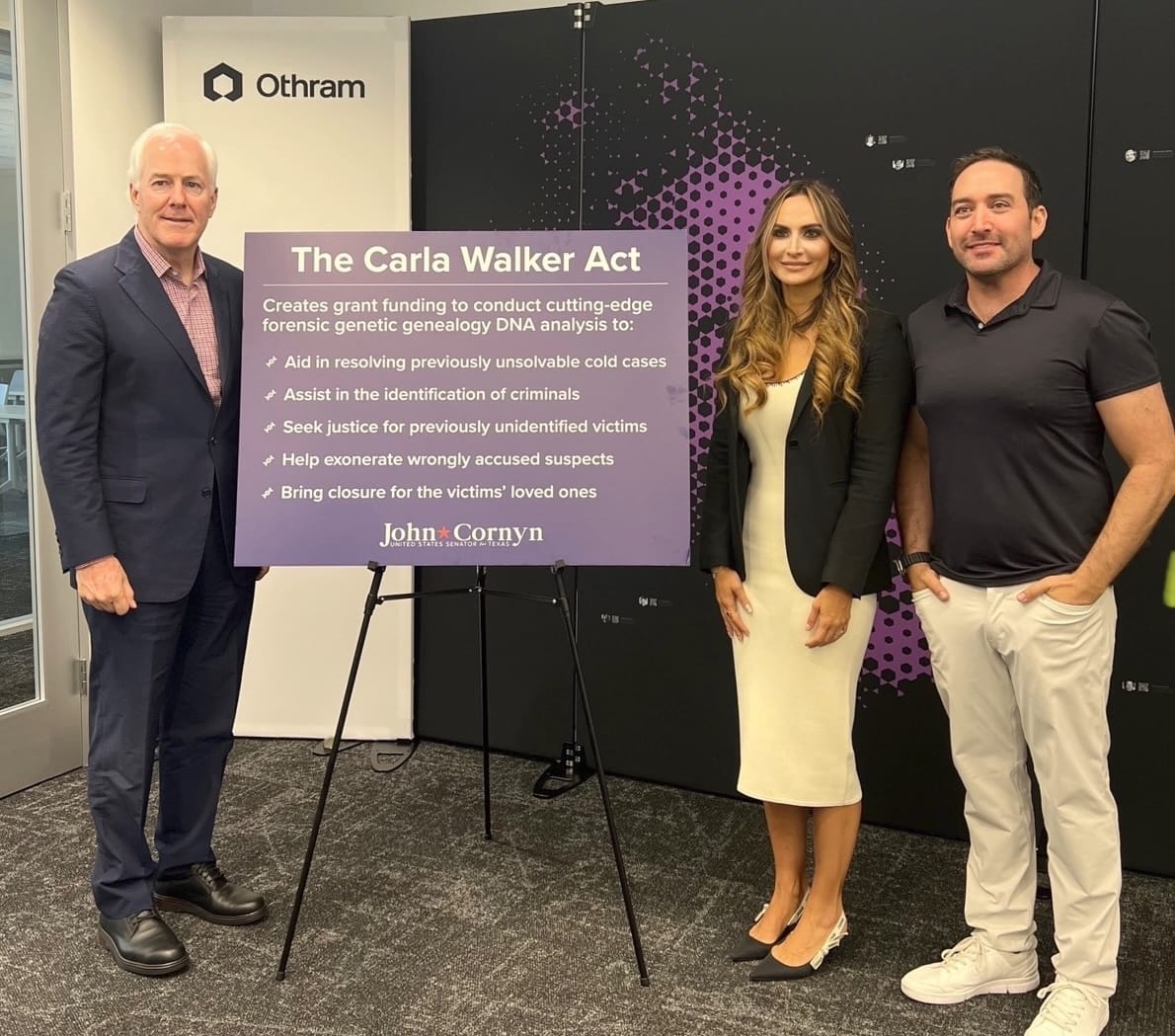

The Carla Walker Act has a history of strong bipartisan backing. In late 2022, Representative Kelly Armstrong initially introduced the bill in the House. The following year, Senator John Cornyn visited Othram to lead a roundtable discussion with law enforcement, victim advocates, and forensic scientists. This meeting served as the kickoff of a deliberative process to explore the needs and opportunities for advancing forensic genetic genealogy. Over the following year, Cornyn’s office gathered feedback from stakeholders, including public and private forensic laboratories, law enforcement agencies, victim advocacy groups, and the Innocence Project. The result was a carefully crafted bill that garnered widespread support from diverse groups with a shared interest in improving forensic science.

In 2024, Representatives Wesley Hunt and Eric Swalwell reintroduced the bill in the House. Armstrong had since resigned from the House to assume the governorship of North Dakota. In the Senate, the bill was introduced by Senators John Cornyn and Peter Welch, further reflecting broad, bipartisan support for advancing forensic science. Notably, all four sponsors—Swalwell, Hunt, Cornyn, and Welch—are members of their respective Judiciary Committees, emphasizing their commitment to improving the criminal justice system.

In addition to bipartisan support in Congress, the Carla Walker Act has been endorsed by several influential organizations, underscoring its importance to the broader criminal justice and forensic communities. These include the Consortium of Forensic Science Organizations (CFSO), DNA Justice Project, Association of State Criminal Investigative Agencies (ASCIA), Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), National District Attorneys Association (NDAA), and the Innocence Project (IP). This coalition of support highlights the widespread recognition of FGG’s transformative potential for solving cold cases, exonerating the innocent, and delivering justice.

A key aspect of this legislation is its focus on transparency and data-driven advancement. Agencies receiving funding through the Carla Walker Act are required to report detailed metrics on their FGG efforts, documenting both successful and unsuccessful cases. This reporting mandate will help build a robust database of best practices, offering critical insights into what works and what doesn’t when analyzing complex forensic samples. Such accountability not only ensures that resources are directed toward the most effective approaches but also fosters innovation by encouraging continuous refinement of FGG techniques.

For two decades, the Debbie Smith Act has provided the funding and infrastructure necessary to bring CODIS testing to the forefront of forensic DNA analysis. The Carla Walker Act has the potential to do the same for FGG, laying the groundwork for this transformative technology to become a standard and indispensable tool in forensic investigations.

Challenges and Opportunities in FGG

While FGG has proven its value in solving cold cases, scaling its use to more cases around the world requires addressing key challenges and seizing critical opportunities. These efforts revolve around four fundamental pillars that form the foundation for advancing FGG:

- Building Ultra-Sensitive DNA Profiles

Forensic samples are often degraded or low in quality, making it essential to build DNA profiles that capture the maximum number of genetic relationships, even distant ones. Ultra-sensitive profiles require comprehensive SNP data, which is crucial for leveraging advanced analytical tools and ensuring reliable outcomes in FGG investigations. - Enhancing Forensic Search Capabilities

Traditional search algorithms are not optimized for the complexities of forensic samples, which may include incomplete markers or DNA mixtures. Next-generation forensic search tools, like those in Othram’s Multi-Dimensional Forensic Intelligence (MDFI) platform, enable investigators to search and analyze even the most challenging profiles with confidence. - Developing Tools to Interpret Genetic Matches

Beyond finding matches, investigators need intuitive tools to analyze relationships, construct family trees, and prioritize leads. Automated and semi-automated solutions, like clustering and triangulation, simplify this process, allowing more investigators to access and benefit from FGG. - Encouraging Public Participation

FGG’s success depends on individuals consenting to share their genetic data for forensic matching. These citizen scientists play a crucial role in creating the genetic connections that solve cases and deliver justice.

Scaling FGG requires innovation in technology, infrastructure, and public engagement. To dive deeper into the challenges and opportunities in advancing FGG, including how these four pillars are being strengthened, read more here.

Conclusion: Advancing Justice with Federal Leadership

The Carla Walker Act represents a significant step forward for forensic genetic genealogy. By funding pilot programs, mandating reporting metrics, and supporting the development of technology, this legislation lays the groundwork for a future where FGG can solve cases that would otherwise remain unsolved. Federal leadership was critical in bringing CODIS to fruition, and it is just as critical now for scaling FGG to address the needs of modern investigations.

As we continue to innovate and expand FGG, community participation remains essential. Every DNA profile contributed to forensic databases strengthens the system, bringing us closer to identifying unknown individuals, solving cold cases, and delivering justice. With the Carla Walker Act, we are not just advancing technology; we are building a future where no case is beyond reach.

In the meantime, we need to keep building tools, publishing research, and solving cases. Our team operates the world's first purpose-built forensic laboratory for forensic genetic genealogy and we can help you solve your case. If you work in a public crime lab, we can help your lab onboard this technology. If you are a law enforcement investigator, medical examiner, or coroner, we can help you solve your case now. We developed Forensic-Grade Genome Sequencing® or FGGS® and more forensic genetic genealogy cases have been solved with FGGS® than any other method.

Let’s work together to unlock answers and bring justice to those who need it most. Get started here.