In criminal investigations, identifying a perpetrator is key to securing justice and resolution for survivors, victims and their families. But what can be done when investigators have DNA evidence linking an unknown suspect to a crime but there is no name to attach to this person of interest? This is where John Doe warrants come into play. These invaluable legal tools can rely on a DNA profile as the identity or descriptor of the unknown donor of a probative evidence sample and have made use of DNA profiles in some jurisdictions for years. These warrants allow law enforcement to file charges against an unidentified suspect and keep cases active—especially critical for sexual assault cases, where statutes of limitations can prevent prosecution if a suspect is identified after the time limits.

While traditional forensic methods have helped link identities to John Doe warrants, forensic genetic genealogy (FGG) is a force multiplier—dramatically increasing the chances of identifying unknown individuals. By combining the power of FGG with John Doe warrants, investigators can preserve cases for future prosecution while leveraging advanced DNA technology to accelerate these identifications with greater speed and precision than ever before.

Othram is at the forefront of this new technology, developing the laboratory and analytical methods that power forensic genetic genealogy as well as publishing open-access, peer-reviewed research to support validity of this work in the courtroom. More FGG cases have been solved using Othram’s technology than any other method, and Othram has presented its work in court more times than any other FGG group—supporting that these identifications are reliable, scientifically rigorous and legally defensible.

What is a John Doe Warrant?

A John Doe warrant is a legal mechanism authorized by a judge and used by law enforcement to file charges against an unidentified individual when investigators have evidence linking an individual to a crime—but no name to attach to that individual. Traditionally, these warrants relied on vague descriptions, such as height, weight, or physical characteristics. However, with the advent of forensic DNA technology the descriptions were made based on a unique genetic profile rather than a vague, often less reliable physical description, which transforms the robustness of the warrant.

How Forensic DNA Testing Transformed John Doe Warrants

The introduction of forensic DNA testing revolutionized John Doe warrants, making them particularly effective in sexual assault investigations, where a perpetrator’s biological evidence is often left at the crime scene. Instead of identifying a suspect through witness descriptions, investigators assign a genetic fingerprint to a John Doe warrant—permitting a case to remain active until the probative DNA profile can be connected to a suspect’s name.

With a John Doe DNA warrant, prosecutors can prevent the statute of limitations from expiring while waiting for new investigative leads. Even if a name is not immediately available, the DNA profile ensures that whenever a suspect is identified—whether through new forensic techniques or even traditional law enforcement methods—the true perpetrator can still be held accountable.

Why John Doe Warrants Matter in Sexual Assault Cases

John Doe warrants are particularly valuable in sexual assault cases, where biological evidence often exists but the suspect is unknown. Many survivors of sexual violence have seen their cases expire before a perpetrator could be identified. By allowing investigators to file charges using an unknown suspect’s DNA as the descriptor, these warrants keep the path to justice open for as long as it takes—potentially for decades.

However, while DNA-based John Doe warrants prevent cases from being closed, they do not on their own identify the suspect. That is where FGG comes into play.

The Role of Forensic Genetic Genealogy in John Doe Warrants

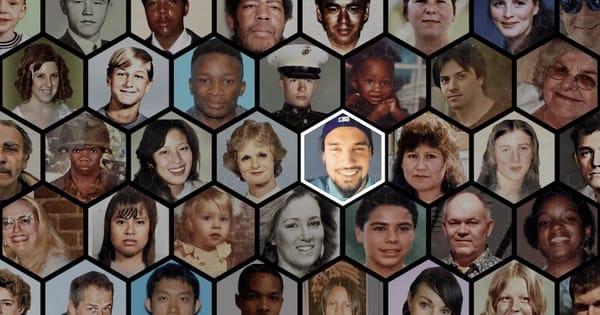

Historically, identification of an unknown perpetrator relied on bringing in persons of interest and using DNA typing to determine in a one-to-one comparison if they were or were not a contributor of probative evidence. With the advent of CODIS identification of persons of interest could be achieved through a CODIS match—but CODIS only contains reference DNA profiles from known arrestees and convicted offenders. If the donor of the probative evidence was never arrested for or convicted of another crime, the individual could remain anonymous forever. FGG overcomes this serious limitation. Instead of waiting for an offender to be arrested and/or convicted to have the DNA profile entered into CODIS, FGG allows investigators to actively search for unknown individuals using the DNA profile from the evidence and those from volunteers who may be closely or distantly related to the evidence donor.

Forensic genetic genealogy works hand in hand with John Doe warrants to proactively identify unknown perpetrators instead of waiting for them to enter CODIS. When DNA from an unknown suspect is recovered from a sexual assault kit or other crime scene evidence, investigators generate a high-density SNP profile, rather than relying solely on the STR markers used in CODIS. This SNP profile is then searched against forensic genetic genealogy databases, where individuals have voluntarily consented to law enforcement comparisons. Instead of providing an immediate suspect name, FGG identifies genetic relatives of the perpetrator, offering critical investigative leads.

Once near or distant relatives are found among these consenting volunteers, forensic genetic genealogists use public records, census data, obituaries, and family trees to narrow down potential suspects. When a strong candidate is identified, law enforcement collects a direct DNA sample for final validation—either confirming a match and leading to an arrest or excluding the person of interest. By combining John Doe DNA warrants with forensic genetic genealogy, investigators no longer have to rely on chance encounters that lead to an arrest; they can actively uncover the suspect’s identity, even decades after the crime was committed.

The Jason Follette Case

A recent case in Maine highlights the immense power of FGG and John Doe warrants. In 1996, a woman in Hancock County, Maine, was attacked and raped in the early morning hours. The perpetrator posed as a police officer, ordered the victim out of her vehicle, and then sexually assaulted her at gunpoint in a wooded area.

Investigators collected DNA evidence, but at the time, forensic technology was quite limited. When no match was found in CODIS, prosecutors filed a John Doe DNA warrant in 2001, preventing the case from expiring under the 15-year statute of limitations.

For more than two decades, the case remained unsolved—until FGG changed everything.

In 2022, investigators worked with Othram to perform ultra-sensitive DNA sequencing on the probative crime scene evidence. The cutting-edge SNP profile was used in forensic genealogy searches, ultimately leading to the identification of Jason Follette—a man whose DNA profile was never entered into CODIS and would have never been found using traditional forensic DNA testing.

Law enforcement later obtained a direct DNA sample from Follette, which yielded a 1 in 36 billion statistical random match probability—linking him to the 1996 sexual assault.

The Follette case is the first prosecution in Maine of a sexual assault case where the suspect was identified through FGG. When Follette was charged, his defense argued that the statute of limitations had expired, attempting to get the case dismissed. However, the Maine judge ruled that the John Doe DNA warrant—combined with FGG—was legally valid, allowing the case to move forward.

This ruling is a landmark decision, reinforcing the legal soundness of FGG-based identifications and demonstrating that John Doe DNA warrants paired with FGG can bring justice and resolution even decades after a crime.

Expanding the Use of FGG in Sexual Assault Cases

The Follette case demonstrates the enormous potential of FGG in sexual assault investigations. For years, John Doe warrants kept cold cases alive, but FGG is the missing piece that allows investigators to more effectively identify donors of crime scene evidence.

This case also highlights the importance of continued investment in forensic science. Federal initiatives, such as the Carla Walker Act, that provide funding for forensic DNA sequencing and FGG, are critical in ensuring that law enforcement has the tools to apply these breakthroughs in more cases.

Additionally, public participation in forensic genealogy databases remains essential. The more individuals who voluntarily upload their DNA for forensic matching, the more cases can be solved, and more survivors and victims can find justice and resolution.

In the meantime, we need to make sure all sex assault cases have access to forensic genetic genealogy and we need to keep solving cases. Othram operates the world's first purpose-built forensic laboratory for forensic genetic genealogy. If you work in a public crime lab, we can help your lab onboard this technology. If you are a law enforcement investigator, medical examiner, or coroner, we can help you solve your case now. We developed Forensic-Grade Genome Sequencing® or FGGS® and more forensic genetic genealogy cases have been solved with FGGS® than any other method.

Let’s work together to unlock answers and bring justice to those who need it most. Get started here.